By Vinnie Santana, ironguides.net

Nutrition has always had a special place for us at ironguides; it’s a way to improve our athletes’ performance and health. In addition to our training approach, The Method—which is based on hormonal balance—all our coaches had always understood that a diet low on carbohydrates, especially when well timed, is the ticket to improving both performance and health with our athletes.

Nutrition has always had a special place for us at ironguides; it’s a way to improve our athletes’ performance and health. In addition to our training approach, The Method—which is based on hormonal balance—all our coaches had always understood that a diet low on carbohydrates, especially when well timed, is the ticket to improving both performance and health with our athletes.

However, we took this approach to another level when I personally was forced to train, live and race under a LCHF (Low-Carb High-Fat) Ketogenic diet for health reasons. The article below is an introduction to my personal experience on this topic, triathlon training on a “keto” diet.

Background

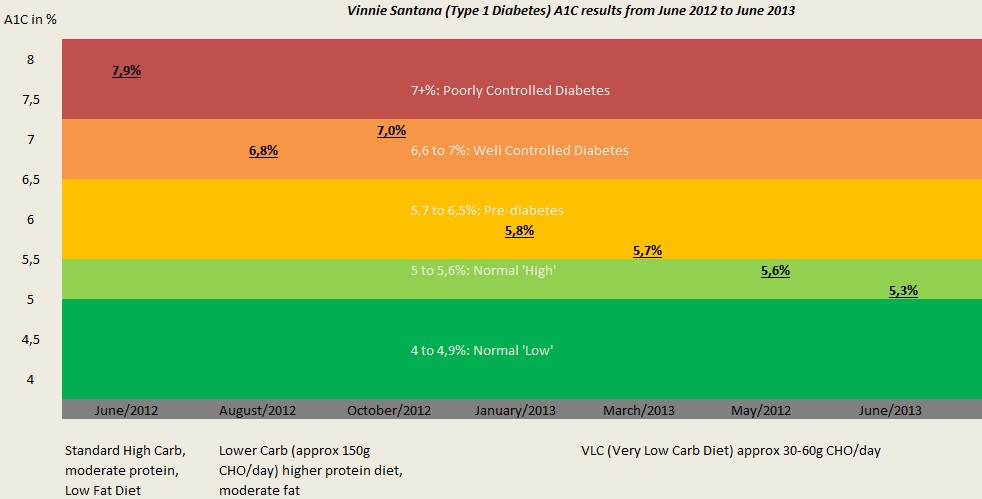

Back in 2000, I was diagnosed with Diabetes Type 1 at the age of 15. People around me wanted to make me feel better and said, “You can still do whatever you want.” With that motto in mind, I continued on my journey to becoming a professional triathlete.

I was managing diabetes as well as I could back then but, due to the lack of adequate information, my diet consisted of the recommended one for high-performance athletes and I tried to cover all that carbohydrate intake with insulin. That did not work so well and my blood glucose levels were running chronically high.

Despite all the challenges, I still managed to turn pro after winning my first Ironman race in 2004. It came full circle when in 2007 I had a PB of 8h50 at Ironman Brazil, which qualified me—as the youngest professional triathlete—for the Ironman World Championships in Kona. My PB also still stands as the fastest time by a Type-1 Diabetic over the Ironman distance.

Then at the end of 2012 I came across a book named “Diabetes Solution” by Dr. Bernstein and he recommended a diet with no more than 30g of carbohydrate per day. The impact on my health was amazing; after only a couple weeks I was seeing blood glucose levels that until that point had been a distant dream. This result created hope that I was now given a second chance with my health and I could carry on with all my other goals in life, as I felt diabetes wouldn’t be a threat anymore.

While I felt great overall, my new diet killed any physical performance I still had—even going up the steps of the local subway station became a challenge. While I didn’t have major plans of racing again, I still exercised on a daily basis and enjoy pushing the intensity here and there, but on that diet, forget it—there were several times I had to walk home from a run, even a slow run.

My work also requires that I train some of my clients in a one-on-one situation. On several occasions I almost got to the point of telling them I couldn’t keep up—and these were beginner athletes, we were running slower than 1-hour 10km pace, a pace I would previously consider slower than a warm-up jog.

To me the message was clear: I had regained my health, but lost my sport. It was a trade-off I could live with but preferred to change. So I kept researching until I finally discovered the world of endurance training on a Ketogenic diet—low in carbohydrates and protein, but high in fat. There was hope again I could continue with triathlon training lifestyle I love.

While there are some resources out there, none of them offered information about a higher-performance racing approach and high intensity training. In theory, Ketosis allows your body to tap into this endless resource of energy stored in your body, named FAT. But it was not clear how well you could perform, at a high level, within this approach.

While I got adapted well enough to get back into doing some exercise, I started to wonder if the athletes I coach could benefit from this diet. So I began to do some experiments in my own racing and training, since my diabetes was now very stable and as an athlete I—unlike my athletes—no longer have pressure to deliver results.

I decided to become my own guinea pig to test what was possible in terms of sports performance on a Ketogenic diet.

While we don’t believe in the magical solution, preferring consistent hard work as the winning formula, a small improvement in performance could make a big difference to some of the athletes we coach—from a more high-performance athlete who is winning smaller ironman races but is not as close to being a threat at the world championships, to the very beginner, but busy, athlete that wants to break a certain time at the next 10km race but has maxed out on his training load.

The theory

There are several books and reputable blogs out there that will cover the benefits of a low carbohydrate diet. I will try to keep this article to the unique information that I can provide based on my experience. But just as a quick intro to sports performance: in theory, being “fat adapted” will provide you the opportunity to use fat as your primary energy source while training and racing, which means that even the leanest athlete still carries dozens of thousands of calories from stored fat and would be able to access to it.

I’ve seen the following analogy that makes things easy to visualize:

- Non-Fat-Adapted Athlete (on a high-carb diet): Is a Petrol Truck that runs out of fuel and has to stop by the side of the road, since he can’t have access to the huge tank of fuel he is carrying. That would be a non-fat-adapted athlete bonking during an endurance event.

- Fat-Adapted Athlete (on a LCHF diet): You develop access to the big petrol container that you carry. The same Petrol Truck won’t run out of fuel since you can now access a close-to-unlimited amount of fuel. Or in the athletic world, you won’t bonk anymore in your next endurance events.

On race day your muscle glycogen will also be used better and reserved only for very glycolytic parts of the race.

There are other benefits too in health—especially addressing the metabolic syndrome issues such as lower blood pressure, improved blood fat levels, weight loss. The other very positive benefits of a Ketogenic diet aren’t necessarily to sports performance: brain function and energy levels. Once both body and mind start to work on a consistent flow of energy, there are no dips. My productivity at work, for example, has improved drastically, but we will save this topic for another article and stick to sports performance for now.

Getting adapted

The term “low carb” comprises a relatively flexible range: less than 150 grams per day is technically low carb, but I went straight into what is considered the lowest, a VLC (very low carb) or Ketogenic, diet, and aimed to keep my carb intake below 30g per day as per the book’s recommendation.

As mentioned, the blood glucose results were nothing short of a miracle and that was the single reason why I didn’t quit this way of eating. While working and other daily activities were fine, exercise was a nightmare: I was feeling horrible for everything from easy jogs to higher intensity workouts, but reading that it would take between two and six weeks to adapt, I stuck with it. In fact, I HAD to stick with it FOR LIFE, so there was nothing to lose. I would just stay on the plan, hoping to feel a bit better in a few weeks down the road.

Six weeks into it, I definitely started to feel better, there were still some off-days on which I would feel completely empty in training, when slowing down wasn’t enough and I had to stop the workout completely. But after about three months, those days wouldn’t appear as often. While there was a slower session here and there, I got back onto a “training plan” and started to do several time trials to track progress in which I tried to keep variables for conditions very stable:

- 5km run on the treadmill

- 400m swim at a 50m pool

- 20km bike in the velodrome

Keep variables consistent while doing tests. Velodrome, treadmill and pool are great facilities for that.

With the above scenario I had the opportunity to track the benefits of several aspects that are supposed to help on a LCHF diet, such as adding electrolytes to the diet to increase blood plasma, Generation UCAN superstarch that releases a very slow carbohydrate into your system, and other general experiments with carbohydrate intake, such as what’s the difference in performance when eating 20g of carbs per day versus 60g of carbs per day.

Fuelling in Training

The whole theory is that you don’t need to fuel in training. However, on the very long sessions fuelling does help to protect muscle mass, keep hunger away after training to avoid overeating and being kicked out of Ketosis, since during training and most of the day you won’t feel very hungry anyway.

At first is difficult to find the appropriate fuel to take in training. I remember I used to make a shake of avocado, coconut milk, nuts, coconut oil, and take it on a bike ride in one of my bottles—right there I had more than 500kcal with very few carbs and would keep the flat flowing through my system.

As you get more experienced and just want to keep things simple, you end up finding your own favourite fuels. These days I enjoy the convenience of UCAN superstarch, packets of nuts, and individually wrapped cheese. I must admit that recipes aren’t my thing, I tend to eat similar things every day and I may need to outsource a recipe book for the LCHF diet. Once you understand the core concept, be creative.

Changes in Body Composition

Staying lean is a challenge for carb-intolerant athletes. Vinnie (white hat) training with Olympic Champion Nicola Spirig at teamTBB.

A nice benefit of a low carb diet, both as an athlete and as an active individual, is the convenience of losing body fat relatively easy.

My whole family is carb intolerant, my father is obese, my mother is borderline pre-diabetic and I have a 2-year-old nephew who has Type 1 diabetes—carbohydrates aren’t our family’s best friend and as an athlete I’ve always struggled to maintain my race weight. I would always train relatively heavy and diet very hard (calorie restriction) in the build-up to my races to lose weight and increase my power-to-weight ratio.

While on Ketosis my weight has been oscillating a lot less, and it has been slowly changing to a leaner and healthier looking body type.

Special attention to high performance training

This part of this article may not apply to 98 percent of the readers; however, there may be two downsides of a LCHF diet for high-performance training that I’m still working on to improve.

- Lack of Glycogen for high intensity training

If you are an elite athlete, a 10km runner for example, you will need to run faster than your race pace at several moments during your race. This is a very glycogen-oriented activity and being on Ketosis may make this type of work relatively difficult.

There are two solutions for this problem: 1. fast running on the treadmill because that biomechanically teaches you how to run faster without the extra aerobic load, and 2. sprint runs on a downhill because that has a similar stimulus.

The same challenge also applies to the swim and bike, for which there are also training methods and tools that can be used to mitigate the downsides.

- Train Low VS Race Higher

Even though your training performance will be very good once you are adjusted, if you go to a high intensity, you will still have the perception fatigue is coming faster and stronger compared with when you are on a high carbohydrate diet. Training tired is hard enough, training tired and low on glycogen can be mentally very draining; it takes a lot of confidence in this approach to know that once race day comes you will be feeling way stronger.

By pulling back your training load (rather than by carboloading), you will get more rest, your muscles will feel fresh and remember that your body is in carbohydrate starvation mode; it will spare every possible gram of glycogen into your muscles, even while you maintain a low-carb diet leading into the race. The result is that on race day you will have a much higher energy level and speed than you are used to in training.

My experience, for example: I could barely break 5:40 on my 400m time trials, then on race day I managed a 5:08—both were done in a pool, that’s a considerable difference!

Racing

There is no substitute for testing your training, equipment, strategy or anything else, than doing the real thing—a real race. After being away from the start line for two years, I decided to put the whole theory to the test and entered several local races.

All were sprint distance that would take me about one hour, mostly in similar conditions in terms of course elevation and weather. So I now had now the opportunity to test the famous carbo-loading theory! In fact there is a little race here in Bangkok that is almost like doing a triathlon inside a gym since it happens in a pool, but you still get the adrenalin boost and the challenge of competition. Below are the things I’ve tested while doing these events:

- Carbohydrate Loading both the day before and race morning

- Protein Loading (to achieve gluconeogenesis, i.e. the body’s generation of glucose from non-carb sources)

- Electrolytes Loading

I wanted to find out how a fat-adapted body could perform on fat only, Ketosis, but with ‘some’ muscle glycogen via protein intake; I also did a relatively high carbo-load (200g on the day before the race). It was also interesting to see the result all those tests had on my diabetes control and blood glucose. Of course I was limited to some of the carbo-load protocol, for example 10g of carbohydrate per kg of body weight, but I’m testing some of these on athletes I coach.

While most of these tests are already done, the more I study and try things, the closer I get to bring out the ideal racing protocol to people on a LCHF. I’m also testing all this on a few of my athletes who are getting ready for Ironman triathlons and marathons. I am aiming to provide an update on the results in about a year.

For now I can say that the difference is very, very small between most of the above scenarios and one can perform very, very fast racing on a Ketogenic diet. I have broken 1 hour in the sprint distance triathlons on Ketosis—while this isn’t a world class time, it’s faster than most triathletes out there.

So, who is this for? Is this for all athletes of all levels?

Everyone can benefit somehow. Some athletes will benefit a lot more, while others need to be very careful with the way they apply the LCHF in their training, otherwise they may be worse off.

This is NOT the magical ticket to success. I remember researching this topic—the message sold was that this was the real deal, rocket fuel that would provide unlimited amount of energy and that I would be able to cruise at my race pace very efficiently without eating any carbs.

You come across testimonials of athletes improving 20 to 40 minutes on their half marathon times and more than an hour on their marathon times. The problem was that this only happened with athletes who were overweight (in relative terms); after losing weight with the LCHF, they went faster mostly due to being lighter, NOT only due to being able to burn fat more efficiently.

So who and how should each specific group use the LCHF? The answer depends on the combination of the length of your event, your performance level and body fat percentage. Below a quick summary of the benefits for each group:

Recreational Athletes – Unless you are very young or part of the lucky ones who won the carb-tolerant DNA ticket, a low-carb approach would bring several benefits, starting at a rapid weight loss, to increasing the ability to burn fat as your primary fuel while training and racing. Since you are also a recreational athlete, your health and wellbeing may also be very high on the priority list; both are two other big reasons to go low carb.

High Performance Age Groupers – It depends on the distance you are training for and competing at, but you certainly want to go to a low carb diet and may time your carbohydrate consumption too during, and straight after, your training. If you are a long-distance athlete, spending a lot of time in Ketosis will definitely bring you benefits on your race day.

Professional Athletes – Can definitely benefit from training periods in a lower carb range, but this should also be timed with the type of work they are doing in each period of the week. The biggest difference to the amateur athlete is the very high intensity training and importance of that on race day, especially from a strategic point of view. At that level, athletes aren’t racing against themselves or against the clock, they are racing their competition. There are times they may be forced to dig deep into their glycogen stores to match attacks and stick to the front group. A fast swim start, for example, can cost an athlete the whole race if they miss the pack, or if an athlete is training low on carbs year around, they may find it more difficult to achieve certain speeds and biomechanical efficiencies that come with it.

Post Lunch in Cape Town with Professor Tim Noakes & Wife Marylin Noakes – Tim is the author of Lore of running and most recent has shifted his focus to Low Carb nutrition and published Real Food Revolution – we discussed at lunch the benefits of LCHF for athletes of all levels, beginners is a clearn benefit, while advanced, they can also metabolize fat at a higher rate even while racing after a certain carboload period

Special Groups – These are usually health related. Diabetics including me are part of this group. Also, if you have any of the conditions listed as metabolic syndrome, you will have huge health benefits (and subsequent performance benefits) of going to a lower carb range.

Conclusion

Do you fit in any of the above categories? Do you think the LCHF approach is for you? Before you make the switch, I suggest you study the topic a bit more and also understand the other health benefits that come with it. In the end this is a change that can improve your performance, health and wellbeing.

Vinnie Santana, ironguides Head Coach

Disclaimer: This article is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical conditions. Information on www.ironguides.net is not intended as a substitute for the advice provided by your physician or other healthcare professional.

–

Train with ironguides!

Personalized Online Coaching: Starting at USD190/month

Monthly Training plans (for all levels, or focused on one discipline): Only USD39/months

Event based training plans:

Sprint Distance (USD45 for 8-week plan)

Olympic Distance (USD65 for 12 week plan)

Half Ironman (R$95 for 16-week plan)

Ironman (USD145 for 20-week plan)

X-Terra (USD65 for 12-week plan)

Running Plans (10k, 21k and 42k – starting at USD40)

Speed up your Ironman Racing with Neuromuscular Resets – Coach Woody

Speed up your Ironman Racing with Neuromuscular Resets – Coach Woody Increase your chances for a Kona slot – Coach Vinnie

Increase your chances for a Kona slot – Coach Vinnie Rest Days and Focus, learn how to read your body and think about what you’re doing. – Coach Shem

Rest Days and Focus, learn how to read your body and think about what you’re doing. – Coach Shem

Recent Comments